On August 8, 2016, Sahiyo conducted its first media training workshop at The Press Club in Mumbai. The workshop was held in partnership with the International Association of Women in Radio and Television (IAWRT), and its objective was to train journalists on how to sensitively and effectively report on the practice of Female Genital Cutting (FGC) prevalent in the Dawoodi Bohra Muslim community.

In the past year, print and television media in India and abroad has played crucial role in reporting and raising awareness about Female Genital Cutting among the Bohras. For decades, the practice has typically been associated with African tribes and was virtually unheard of in India. So far, the Bohras are the only community known to practice khatna in India and for many, it has come as a shock that this small, otherwise-progressive sect follows a tradition that is internationally recognised as a human and child rights violation.

Given this context, news publications in India have taken active interest in breaking the silence and secrecy around khatna through interviews, reports, features and news documentaries. FGC, however, is a very complex and controversial issue that requires well-informed and nuanced reporting that is sensitive to the survivors and communities involved. This, at times, has been amiss.

News coverage of khatna among Bohras has been well-intentioned but often, journalists unwittingly misunderstand and misrepresent facts about the practice, and/or portray the issue in a sensational manner that can end up harming FGC survivors, girls at risk and the movement at large.

Sahiyo realised that this could be addressed only by generating more awareness amongst journalists about FGC in the Bohra community and the pros and cons of various styles of reportage on the issue.

Nearly 30 journalists attended the workshop that Sahiyo conducted on August 8. The workshop included a brief screening of Priya Goswami’s segment from the IAWRT 2015 Long Documentary Reflecting Her, which gave participants a quick visual introduction to the way in which khatna is practiced by Bohras.

In sessions conducted by all five Sahiyo co-founders, the workshop emphasised the importance of the media in impacting social change and attempted to chalk out certain do’s and don’ts for journalists, writers, filmmakers and other artists interested in working on the practice of khatna.

Why the media needs to be sensitive

Sahiyo co-founder Mariya Taher, for instance, spoke about how the media sometimes ends up harming and jeopardising efforts to end gender-based violence, by compromising the safety and interests of survivors, by reinforcing myths and stereotypes, or by sensationalising stories. To ensure the safety of a gender-based violence survivor, the media must not only respect privacy and confidentiality but also consider the retribution survivors could face if their safety is compromised.

Khatna, like many other traditional and cultural practices, is a social norm that people have followed over time because that is the acceptable thing to do in that society/community. It is important, therefore, that the media doesn’t end up vilifying the community for practicing this social norm – something that many media reports unintentionally tend to do by using words like “brutal”, “barbaric” and “gruesome” to describe khatna.

These terms are judgemental, much like the terms “mutilation” and “FGM”, and Sahiyo has consciously chosen to refer to the practice as female genital cutting or FGC instead. (More on Sahiyo’s use of terminology here.)

The importance of visuals and factual accuracy

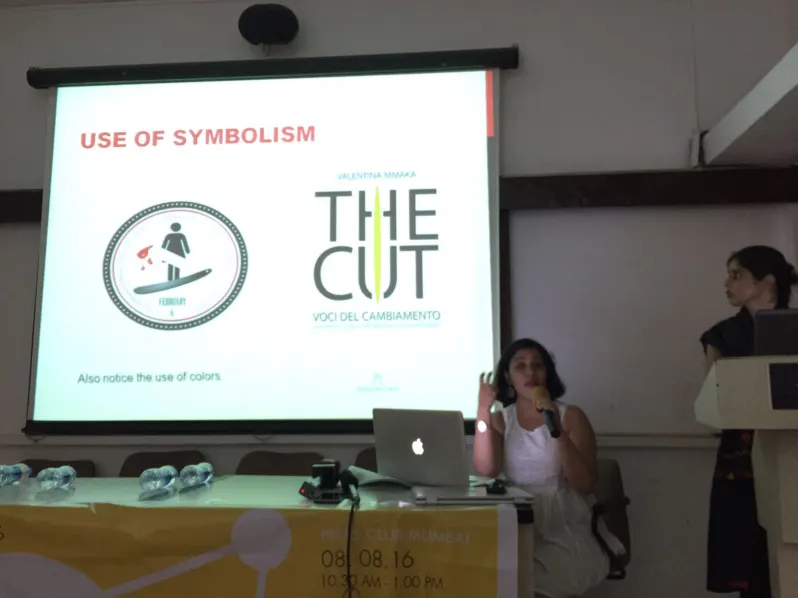

Priya Goswami’s session focused on the pros and cons of using various types of visuals to represent FGC among the Bohras.

Most media reports on khatna are accompanied by visuals that typically depict bloodied blades, female figures cut by blades or even stitched up vulvas. These visuals often end up evoking feelings very different from what the journalist or designer may have intended. The intention may be to sensitise readers/viewers, to evoke empathy with survivors, to build dialogue and to bring about change. Instead, such blood-and-gore visuals often merely have shock value and end up alienating the community.

They may also end up triggering additional trauma for survivors. Journalists could instead consider using milder, less blatant symbolism in visuals related to FGC.

It is also important that generic photographs used in media reports on khatna must not compromise the identity or invade the privacy of individual community members – journalists could use generic images that showcase the community without highlighting individual faces.

Aarefa Johari’s session highlighted various factual errors that reporters unwittingly tend to make while covering FGC. A major example is when journalists misrepresent the health consequences of Bohra-style khatna (Type 1), by mixing it up with the consequences of other, more severe types of FGC practiced by other communities. Or when media reports generalise the depiction of the way in which khatna is performed on Bohra girls, giving readers the false impression that all girls are held down and cut in dingy rooms by untrained midwives. In reality, khatna is experienced in myriad ways by different Bohras and these differences need to be acknowledged and represented.

Sahiyo looks forward to continuing dialogues with both the community and the media in this important journey to abandon the practice of FGC.

To see the full report on the Media Workshop, click here.