by Debangana Chatterjee

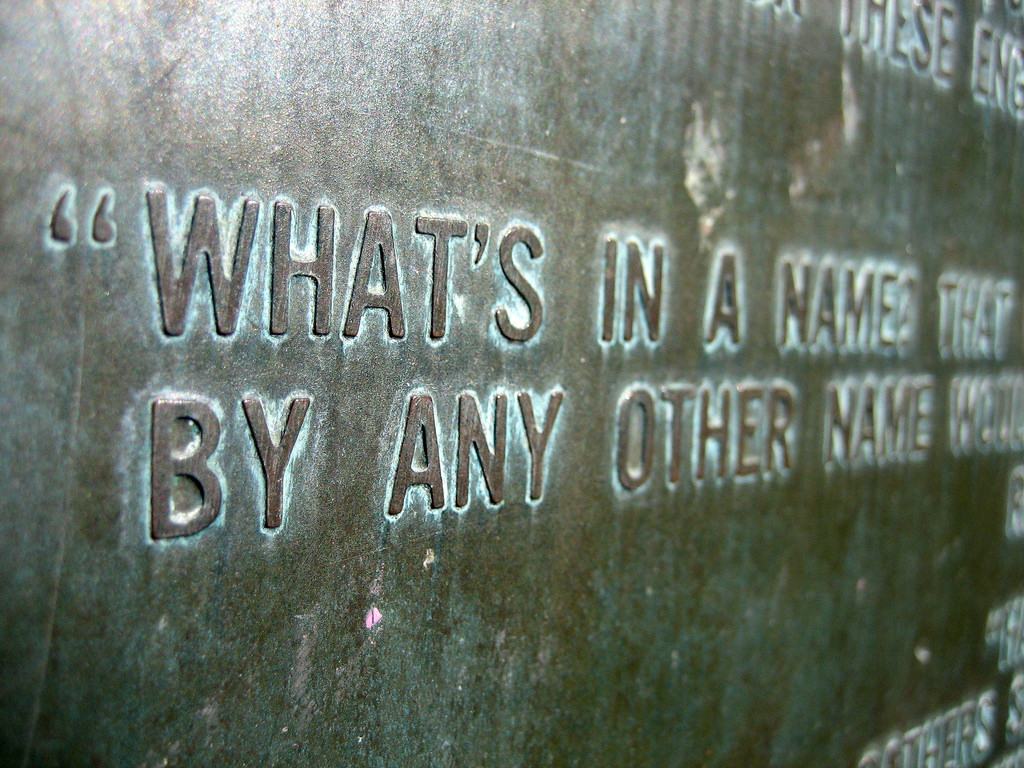

Two years back when I ventured into trying to understand a culturally specific embodied practice pertaining to procedures involving partial or total removal of the external female genitalia ‘for non-medical reasons’ as a researcher, the biggest challenge for me was to ‘call it by the name’.

Disagreements regarding the usage of the term ‘mutilation’ in Female Genital Mutilation (FGM), bearing a negative connotation, have surged. International organisations and agencies commonly term it FGM. The World Health Organization’s (WHO) justifies usage of the term on the basis of its previous reference in 1997 and 2008 by the interagency statements. WHO also acknowledges ‘the importance of using non-judgemental terminology with practising communities’ and some of United Nations agencies prefer adding the word ‘cutting’. Ultimately, both terms underline the violation of women and girls’ rights.

‘Mutilation’ refers to impairing a vital body part by cutting it off with an explicit intent to harm. In this context, a few other terms used to connote FGM require closer attention. Female circumcision and excision are often used identically with FGM, although these do not fully carry the information regarding the practice. Out of the four types of procedures entailing FGM as specified by WHO, female circumcision appears akin to type I and even occasionally type II FGM and appears not as physically severe as the Type III category. Yet, existing research suggests that treating female circumcision as replacements for FGM fails to take the practice into account in its entirety. Using ‘female genital surgeries’ is contested as well, as it appears to validate medicalisation of FGM or in other words implies that FGM is a medical surgery like other standard surgeries.

The term FGM received significant prominence in the 1990s. Fran Hosken coined the term in 1993 to draw international attention to the ill-effects associated with the practice as well as to distinguish it from the widely prevailing male circumcision practices. For Ellen Gruenbaum the term ‘…implies intentional harm and is tantamount to an accusation of evil intent’ and thus, entails greater chances of hurting sentiments. There are scholars like Stanlie M. James and Claire C. Robertson who prefer Female Genital Cutting (FGC) instead of FGM. They consider ‘circumcision’ insufficient as it makes a ‘false analogy’ to male circumcision. At the same time, they disagree with the term FGM as it subsumes that all types of the procedure are an act of ‘mutilation’. Anika Rahman and Nahid Toubia also choose the understanding of FGC and circumcision as to not force women to dwell on their body as mutilated. These scholars understand the sense of trauma that ‘mutilation’ might connote for some women.

In fact, the constant reference of FGM in the existing international human rights (IHR) discourse mostly remains unaware of other forms of bodily mutilation of women. ‘Mutilation’, in this sense, can mean both bodily modifications attempted through cosmetic surgeries and public sexual violence which remains under the sovereign jurisdiction of the states concerned. Needless to say, mutilation of raped bodies is one of the most common occurrences of sexual violence. When FGM as a cultural practice is emphasised over other forms of ‘mutilation’, it indicates the cultural biases of IHR discourse. It is not to dilute the abhorrence that this practice deserves, but to show how little a space it leaves for consciousness building and community learning. For both the activists and researchers alike, extreme caution is required to not alienate people and to sustain the dialogic engagement with them.

Also, with ‘mutilation’, a popular imagery of infibulation (narrowing of the vaginal orifice) is attached. It comes more with its representation in popular culture as is the case with the film Desert Flower. Notwithstanding the reality of the incidence shown in the movie, in most of the cases, the type I and II procedures are conducted instead of type III (infibulation). Clubbing all the procedures under the single rubric either exaggerates type I and II FGM or dilutes the gravity of Type III and some forms of Type IV (Type IV includes miscellaneous procedures like piercing, pricking, incising or stretching of the clitoris, burning or scraping of vaginal tissues. Whereas some of the type IV procedures are of greater concern, others may not necessarily appear as severe).

In the light of these debates over terminologies, how does a researcher resolve her dilemma?

My study aims to locate the practices of FGM/C exclusive to the Bohra Muslim community in India in the frame of international politics. Especially keeping in mind my position as a scholar who is outside the purview of the culture, I stand on the edge of being either called a cultural relativist/apologist (a person who believes that people’s cultural traditions can only be judged by the standards of their own culture and thus, cultural practices are to be judged relative to the understanding of its practitioners) or prejudiced against cultural particularities. My study aims to juxtapose international discourses surrounding the practice vis-a-vis its occurrences in India. Hence, while writing my thesis, I shall be using FGM interchangeably with FGM/C to reflect the larger WHO definition and its usage in the international circle. As no term seems perfect in defining the practice, academically FGM/C looks commonly acceptable reflecting the international outlook towards it. Needless to say, the term FGM/C also has received substantial backlash from the communities and Bohras are no exception to it. An objective and unbiased study of the practice seeks the right approach more than an elusive perfection in terminology. Thus, during my interactions with members of the community, while analysing the local Indian discourse, khatna as a term will be given preference respecting the cultural uniqueness that the term bears.

More about Debangana

Debangana is a doctoral scholar at the Centre for International Politics Organisation and Disarmament (CIPOD), Jawaharlal Nehru University. Through her research, she is trying to locate the existing Indian discourse surrounding the practices of FGM/C and Hijab into the frame of international politics. If you would like to connect with Debangana, you can reach her at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..