By Debangana Chatterjee

A journey through religious texts helps us to validate or disprove the claims that there are religious justifications for traditional cultural practices. A similar logic applies to the claims that Female Genital Cutting (FGC) is an Islamic practice.

The Holy Quran and the hadiths, evolving from the deeds of the Prophet Muhammad, form the basis of Sharia or the Islamic law. Whereas the Quranic scriptures are unquestionable, hadiths require authentication as they are the dynamic source of evolving Islamic practices. Hadiths are the Prophet’s verbal instructions which were documented by various narrators after the Prophet’s death. The actual narration of the text is called the matn and the insad contains the trail of narrators to support the authentic transmission of Prophet’s instructions over generations. Hadiths can be classified as either mutawatir or ahad. Mutawatir hadiths are substantiated and backed up by multiple reporters documenting his guidelines and thus, is adequately acknowledged within the Islamic circle. Praying namaz, donating, fasting and going for Hajj are few of the mutawatir hadiths which are considered fully authentic. On the contrary, although a few ahad hadiths are thought to permit a limited form of female genital cutting, they are deficient of authenticity borne through insad.

According to a Baihaqi hadith, circumcision ennobles women. But many suggest it to be advisory rather than obligatory. One of the Bukhari Sharif hadiths considers circumcision as one of the acts of fitra (human acts inspired by God) like the removal of pubic hair, trimming the moustache, removing armpit hair and shortening nails. In Islam there has been much controversy whether fitra is binding. One Jami at-Trimidhi hadith suggests that there must be an essential bath after sexual intercourse between the two circumcised genitals of opposite gender. Though the supporters here take circumcision as a prerequisite to sexual intercourse and hence to marriage, the commandment of the hadith lies at the fact of taking a shower after sexual intercourse where circumcision may be spoken of as a natural presupposition. Written in Arabic, this hadith may have been toldto a community that was culturally inclined towards FGC at the time it was said. Hadiths by Abu Dawud, Al-Tabrani and Al-Khatib al-Baghdad seem to suggest conducting a plain cut of the clitoral prepuce, as according to them it beautifies a woman’s face and makes her even more desirable to her husband. Primarily even if the hadith indicates FGC, it eliminates the severe forms of it such as infibulation and only promotes the least severe form.

Other interpretations of this hadith suggest that rather than taking it as the Prophet’s order, one may read this hadith as suggesting it is merely a desirable option. In contradiction, a hadith reported by Abu Sa’id al-Khudri and documented by Ibn Majah and Al-Daraqutni with an authenticated line of insad seems to unequivocally reject any practice amounting to harm.

In Shia Islam, taharat (purity) concerning the notions of hygiene, cleanliness and purity is sometimes put forward to justify FGC. It is believed that due to the clitoral unhooding the excess building up of smegma is addressed. Yet, effective measures of washing and cleanliness are more than adequate to address this issue. Removal of healthy tissues for it does not seem to be credible enough.

In India, Dawoodi Bohras, the largest Bohra sect belonging to the Tayyibi Ism’aili branch of Shia Islam, who practice khatna, consider the Da’i al-Mutlaq, also known as Da’i, to hold an authoritative, infallible status in the community. As the Da’i considers Daim-ul-Islam as the binding religious text for the Bohras, diktats of the text are taken as truth by devout community members. In this text, the Prophet is believed to advise for a simple cut of a woman’s clitoral skin as this, according to certain translations of the text, assigns chastity to a woman and makes her more ‘beloved by their husbands’. Though supporters of FGC cite this as the reason for the continuation of khatna, scholars have shown that da’is have never been as invincible historically, as has occurred in the recent past. In fact, changes in the provision that khatna is required, would add dynamism to the religion.

Islam as a whole neither complies with the practice nor endorses FGC. Despite repeated invocation of religious references as a justification for FGC, considering the myriad number of Islamic texts, the grounds for such justification hold little or almost no merit.

Read Part 2 – Female Genital Cutting (FGC): Is it an Islamic Practice?

More about Debangana

Debangana is a doctoral scholar at the Centre for International Politics Organisation and Disarmament (CIPOD), Jawaharlal Nehru University. Through her research, she is trying to locate the existing Indian discourse surrounding the practices of FGM/C and Hijab into the frame of international politics. If you would like to connect with Debangana, you can reach her at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..

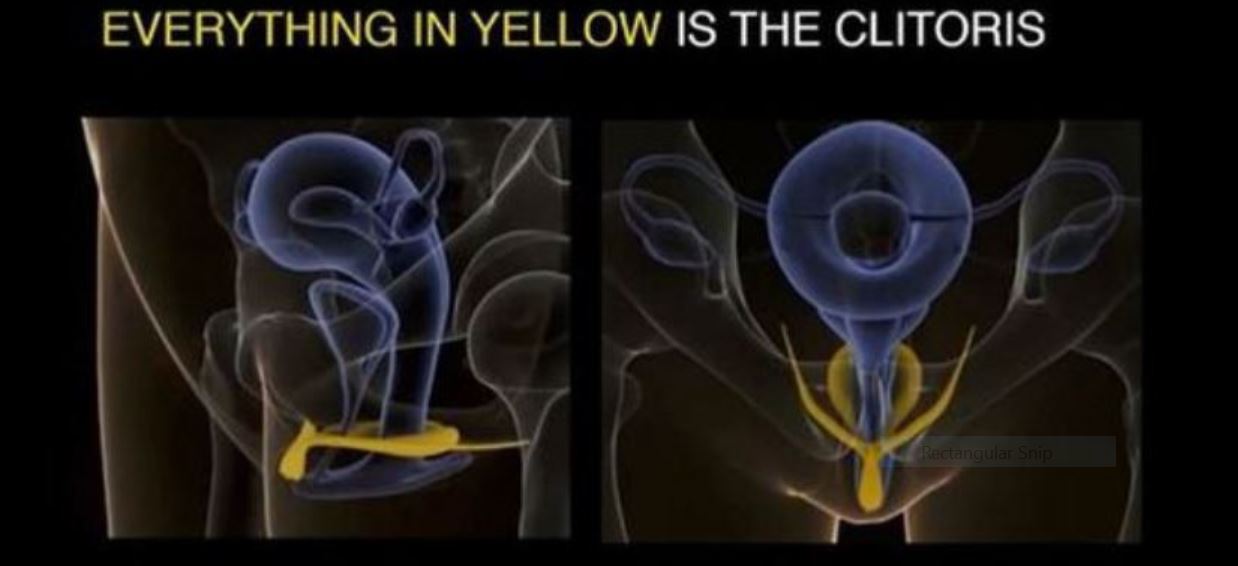

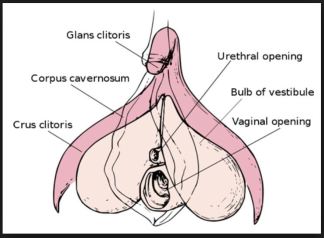

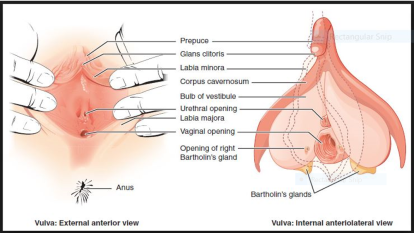

The issue of clitoral anatomy is also significant concerning the practice of clitorectomy.

The issue of clitoral anatomy is also significant concerning the practice of clitorectomy.  About Joanna Vergoth:

About Joanna Vergoth: