By Anonymous

Age: 26

Country: United States

(Read the Hindi translation of this article here.)

I remember hearing about it for the first time in my Saturday school class. A male teacher was taking our class that Saturday morning, and the topic was circumcision. At the ripe age of 14, I didn’t really know what that meant, but I did know it involved something that was related to sex-ed. I awkwardly sat with the girls in my class on the right side of the room, separated from the boys by a wide space, who sat on the left side of the room. The teacher began to speak about male circumcision; that skin was surgically removed from a boy for hygienic reasons. He then went on to explain female circumcision; that it was done to curb a girl’s sexual desire. Girls were meant to be chaste, quiet, and obedient. Circumcising little girls was the only way to keep them from being promiscuous. It was the only way to stop them from bringing shame to their families.

I remember sitting there, having no idea what my teacher was talking about. I was sure I had never undergone this procedure, or whatever my 14-year- old brain could comprehend from the Gujrati he was speaking – it was not my first language. I felt extremely uncomfortable and unsettled as I sat in that room that day.

I remember going to a sleep-over at an older girl’s house that same Saturday, where the topic inevitably turned to what we had heard at Saturday school earlier that day. I sat quietly as one girl, a bit of a know-it-all, explained why this procedure was done on girls, and how it made us better Muslims and better Bohris – because circumcision ensured that we would never be tempted by sexual desires and pre-marital sex; it cleaned us, purified us. I listened intently as other girls relayed their circumcision stories, all the while feeling like a fraud because I knew that I had never undergone this “rite of passage”. I know now that I still didn’t understand then, what this rite of passage truly meant. All it meant to me was that I didn’t fit in, that I was a “bad girl”, that I was dirty, and that I was just pretending to be a good Muslim.

I remember finally working up the courage to ask my mom about it a few weeks later. I watched awareness dawn in her eyes, as I relayed what we had learned in class. I saw the look on her face when I hopefully asked her if I had had this procedure done, and just didn’t remember. She shook her head. She had always meant to take me to get it done, when we were in India but had just never gotten around to it. I told her the stories I had heard from my friends and asked her if she could explain this procedure to me since I had had trouble understanding it in my class. She proceeded to explain the process of khatna to me; the removal of skin from a girl’s clitoris, to make her clean and pure. As I heard the explanation, I cringed. She watched me for a few minutes and then stated with authority that the next time we went to India she would take me to my aunt, a doctor, who would perform the procedure on me. I sank to my knees in front of her, begging her not to do this to me, begging her not to make me undergo what sounded like an unimaginably painful procedure. I promised her that I would be good, I would be clean, I would do anything she wanted if she would just forget this whole thing. She exhaled, saying “we’ll see” in a soft, resigned voice.

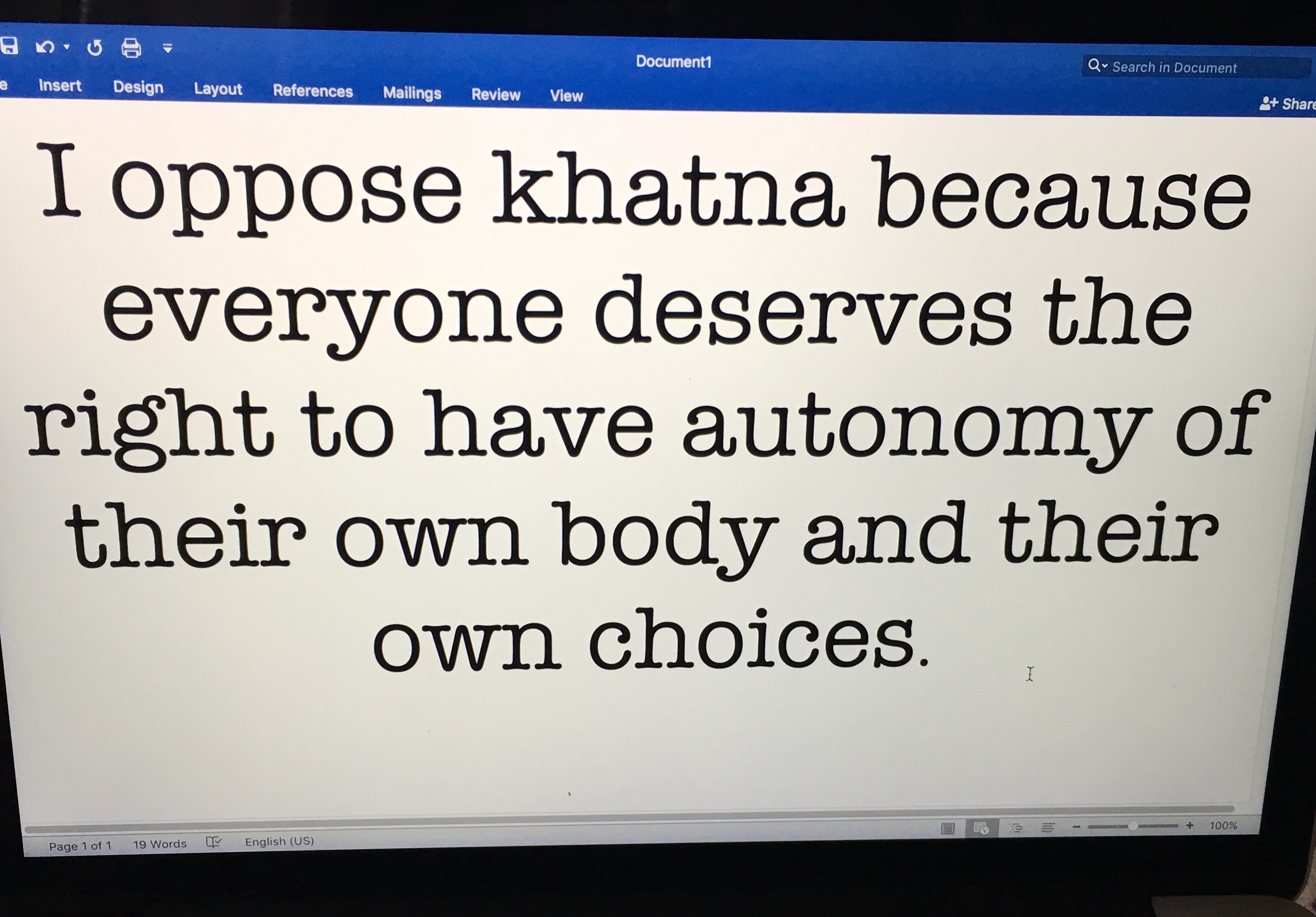

I remember getting older, doing more research on what khatna even meant, listening to my cousin passionately talk about how wrong it was, and realizing what a monumental loss my mother had spared me from. As an adult, I view the practice of khatna very differently than I did as an impressionable teenager. So many young girls have had this choice stolen from them.

No one has asked them if this is something that they want. Their families have decided to steal a part of who they are, without any regard for what it will do to them, and often times make the decision to bring their precious little girls to unsterile and inexperienced hands to do something so serious to their bodies.

I remember seeing a huge Facebook discussion break out months ago, where a very outspoken girl I know accused people who work to stop khatna of “airing the dirty laundry” of the Bohri community in such a public way. In that moment I had never felt so much shame at someone in my community. This practice is wrong, and the non-consensual nature of it makes it even more heartbreaking and deplorable, to me. When your community is doing something questionable and touting it as a religious practice revered by the Prophet (PBUH), you don’t close ranks and hide deeper in the shadows. You open the floor to debate and discuss how we can become better as a community. You discuss how we can protect the young girls and young women of our community and give them the chance to make their own choices, rather than taking their choices away from them.

We can do better as a global community to stop this. My mother saved me. She put her love for me first, and I am the woman I am today because of her. I am forever grateful for her protection and guidance. All young women deserve the same protection, the same love, the same respect, and the same autonomy over their bodies. It’s the least we can do.