Last week, many Dawoodi Bohras around the world received the link to an online “research” survey with questions about Khatna/Khafz practiced in the community. Khafz refers to cutting a portion of a girl’s clitoral hood – a type of Female Genital Cutting – and this new online survey by Dr. Tasneem Saify, Dr. Munira Radhanpurwala T and Dr. Rakhee K claims that it aims to get feedback from Dawoodi Bohra women and men about the practice. (Link to survey is here).

As someone who has gone through the process of designing multiple research studies, I can confidently say that this latest survey on Khatna/Khafz in the Bohra community is neither a safe nor an unbiased tool for conducting proper research on female genital cutting. Other academic researchers who reviewed the Khafz survey have also pointed this out. For example, Usha Tummala-Narra, Ph.D., an associate Professor in the Department of Counseling, Developmental and Educational Psychology at Boston College, states:

“The questions are strangely worded, and implicitly and explicitly suggest that the practice is not mutilation or traumatic. There are also no questions related to girls’ or women’s experiences of the practice. We can’t really know much about the definition of khatna/khafz without asking about the experience and its effects over time.”

While Karen A. McDonnell, an Associate Professor and Vice-Chair in the Department of Prevention and Community Health at Milken Institute School of Public Health at the George Washington University, states:

“Overall this survey presents itself as a feedback mechanism from Dawoodi Bohras about female circumcision. Taking the perspective of someone trained in objective survey development in psychology and public health, the survey actually reads in its entirety, not as a feedback, but rather as a tool for marketing a perspective. As the survey proceeds, the tenor of the questions increase in a lack of objectivity and a central cause/message is quite clear and the respondent is made to feel manipulated.”

While all research has its limitations, the design of this questionnaire suggests that it clearly was NOT created and sent out into the world to collect empirical unbiased research on the practice FGC/Khatna/Khafz. Instead, the bias and manner of wording of this survey tool express that the authors (Dr. Tasneem Saify, Dr. Munira Radhanpurwala T & Dr. Rakhee K) are seeking responses that will justify their motives to prove that Female Genital Cutting (FGC) does not harm girls.

Which makes me wonder, was this research tool (the survey) even vetted before the study’s implementation?

In 2008, because of my increasing passion to end violence against women, I choose to craft and carry out research for my Master of Social Work thesis on “Understanding the Continuation of Female Genital Cutting Amongst the Dawoodi Bohras in the United States.” The issue had been in the recesses of my mind for years and I wanted to learn how a practice that involves cutting the sexual organs of a young girl could ever have been deemed a religious or cultural practice. I wanted to understand how the issue of Female Genital Cutting (FGC) could continue generation after generation without question, because if I could understand this reasoning, then I could better understand why FGC had been done to me at the age of seven.

As a graduate student, my thesis advisors walked me through every step of the research process, from consulting references and existing studies, to contacting other academics and experts who had studied FGC. In the end, I carried out an exploratory study and crafted questions that could be used to conduct ethnographic interviews. Ethnographic interviewing is a type of qualitative research that combines immersive observation and directed one-on-one interviews. In order to draft the questions, I consulted questions used in previous studies by other researchers. My thesis advisors reviewed the questions, and the San Francisco State University’s Institutional Review Board examined my question to ensure there was no hidden bias in the wording of my questions that could lead participants to answer one way or the other.

Having been through the process once, and understanding the importance of having multiple individuals review your questions for hidden biases, years later, I went through a similar process when Sahiyo designed its study on Khatna among Dawoodi Bohra women. Prior to engaging Bohra women for the study, our research tool (the survey) was vetted by many NGOs and expert researchers.

If this newest Khafz questionnaire by Dr. Tasneem Saify, Dr. Munira Radhanpurwala T & Dr. Rakhee K had been vetted by other individuals and institutions, it would have recognized the following problems well before releasing the study to the public.

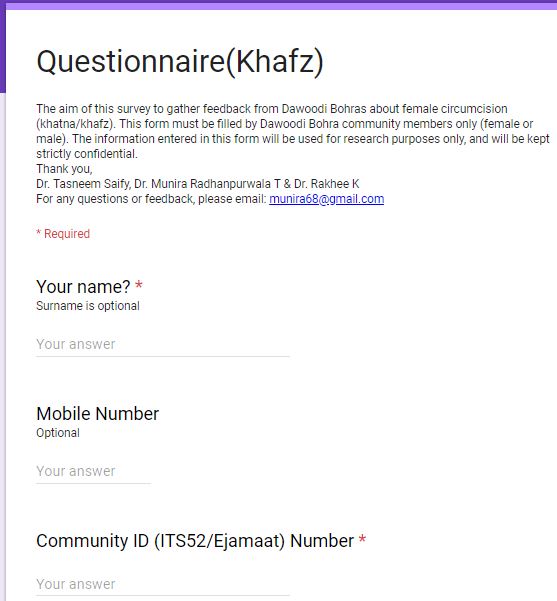

1) Participant consent

Prior to filling out a study, it is important that participants are informed of the study’s intention and are able to sign a consent form acknowledging that they understand the study’s purpose and are giving their permission for the findings to be used in a study’s report. The new Khafz -survey does not have a consent form that does such. [See Screenshot to the left]. In fact, the purpose of this survey is misleading to the reader. There is no mention of how the respondents are being recruited and if their responses will be anonymous or even held in confidence and in essence violates a respondents rights as a participant.

2) Confidentiality

The new Khafz survey form requires participants to provide information that will NOT allow their information to remain private. The study requires that participants add their Community ID (ITS52/Ejamaat) Number. As reported in Mumbai Mirror, the ITS number keeps track of a Dawoodi Bohra’s personal details, including the number of times a person visits the mosque. By requiring an individual to enter this information, already the researchers have directly violated a person’s right to privacy. The question also limits respondents to only those who have signed up for such an ITS number. This, therefore, rules out the participation of many individuals born into the Bohra community or to a Bohra parent who may not have signed up for the ITS card for a variety of reasons, but who have had to undergo FGC as children because of a decision made by a family member or community member.

The mandatory requirement of disclosing one’s ITS number can also discourage an individual from filling out the survey for fear of backlash from the religious community for disagreeing with the practice of Khafz Such backlash occurs on a regular basis against advocates speaking against FGC as can be viewed on Sahiyo’s social media accounts. (See Sahiyo Activist Needs Assessment to learn more about the challenges individuals face when they speak in opposition to FGC).

3) Biased questions

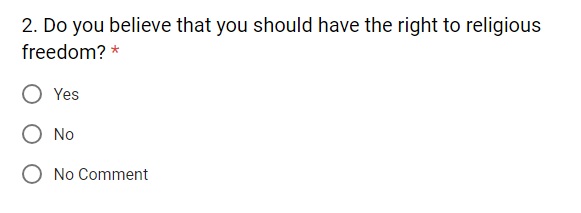

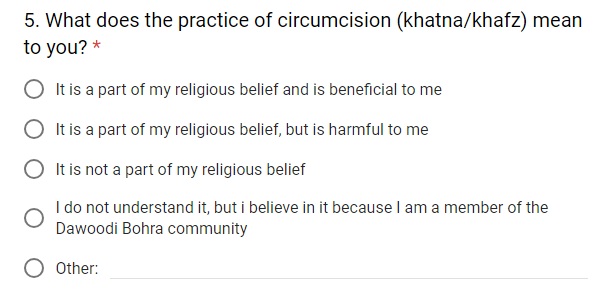

Besides the problematic ITS number, the wording of subsequent questions on the new Khafz survey is biased and considered to be leading questions that prompt survey respondents to answer in a specific manner.

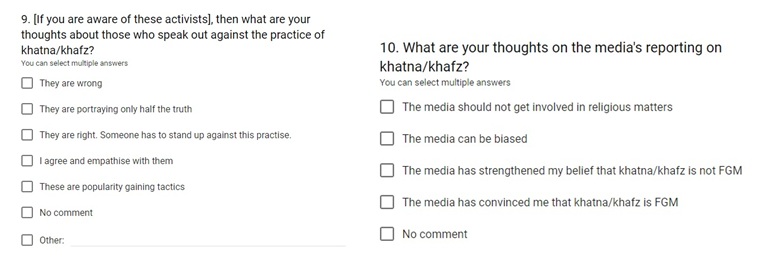

For instance, Questions 2, 5, 9, and 10 make assumptions about religious freedom, media, and activists, rather than posing the questions and response choices in a more neutral, open-ended form.

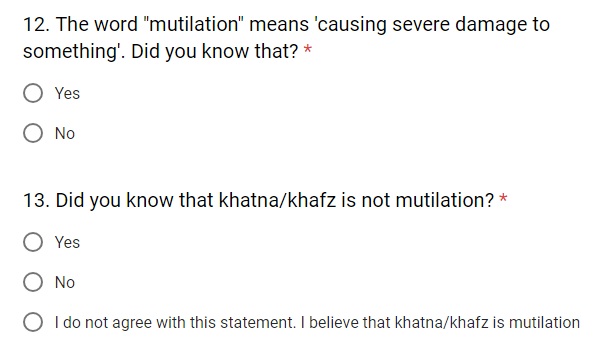

Questions 12 and 13 are perfect examples of problematic, leading questions: Question 12 offers a definition of the word “mutilation” without any context to why the word is being asked. Question #13 then frames the question in a manner that can minimize or under report a participant’s level of distress associated with khatna/khafz, and also automatically suggests to the participant that the practice is not mutilation.

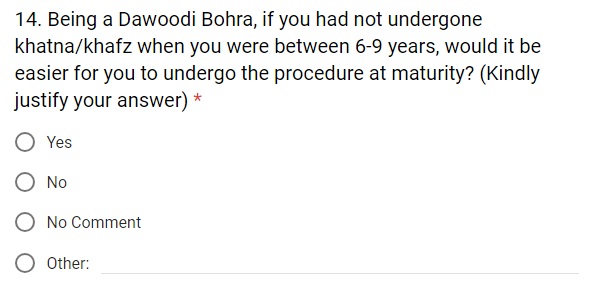

Question 14 is confusing for another reason. The introductory paragraph by the researchers suggests that male participants can take part in the study, however, Question 14 is written and geared towards female participants who undergo Khatna/khafz.

Yet, because of the asterisk (*), the question is mandatory for all respondents, meaning men would have to submit a response to Question #14. This inclusion of information would automatically invalidate the data collected as men have NOT gone through khafz. The wording of the question also infers that all Dawoodi Bohra women have undergone khatna/khafz, which, from anecdotal reports and previous research on FGC in the Bohra community, we recognize is not the case. In fact, we do see a trend in the Bohra community of people wanting to give up the practice on future generations of girls. Yet, the survey makes no mention of this trend or suggests that it is even an option amongst survey respondents.

Overall, the Khafz/Khatna study is problematic for an entire milieu of reasons, not only the ones I have listed here. However, as a researcher, a social worker, and a woman who has undergone FGC because I was born into the Bohra community, what saddens me the most about this survey is that it is yet another attempt to discredit and disbelieve the numerous women and girls who have spoken up and stated that FGC was harmful to them. These women have spoken up for no other reason than to be believed, and instead of comforting them, the researchers of this new Khfaz/Khatna questionnaire are trying to silence them.