By Anonymous

I am a survivor of childhood sexual abuse. Though for much of my life, “victim” felt like the most honest word. Those experiences have shaped my relationships, both to others and with myself, so that forging an identity outside of that trauma is an impossibility. What happened to me exists in public court records and it is known within and outside of my community; it is the thing we don’t talk about at family dinners. So, when I thought of myself, what it meant to be me, “victim” was always near the top of that list.

Despite years of therapy, some things are still very hard for me. Some days I am driven by a nameless panic, shaking hands and speeding thoughts and all. Others are much worse than that. A patient, well-deep sadness that I don’t think I will ever be entirely free of. My body often feels like a thing separate from me, such dissociation is not uncommon. The complexity of mental health is never lost on survivors; some days are bad, others are calm and joyful. That’s the journey, and this is a thing I carry. It’s heavy, but I do.

When I found Sahiyo, I knew immediately that this was an organization I wanted to be a part of. I knew it would be healing but as any survivor knows, healing can be painful, too. I knew it would challenge me, force me to examine deeply uncomfortable truths. This was an opportunity to observe where my hesitations were coming from. I wanted to become comfortable talking about women’s bodies, about trauma, about health and wellness—all of the things we so gladly tuck away.

So in those early days, that’s all I did. I read Maasi blogs, which handled trauma with grace, patience, and accessible resources. I (safely and mindfully) pushed myself to really look at the language and how it was being used. I focused on my body's responses as I read words I would normally avoid: cutting, labia, orgasm, vagina, genitals, clitoris, consent. I read the stories of survivors, and I held space for their pain, grief, anguish, and their bravery. Over time I realized that so much of their narratives mirrored my own experience.

Like them, I knew as a child that something had happened to me. I knew that I was one person before those experiences, and another afterward. Even as a child, I knew that my body now carried the weight of trauma. But like some survivors of female genital cutting, I would reach for the memories and come up with nothing but flashes of pain. Mostly empty air. Whether my mind was protecting itself, or those memories never formed due to particular details of the events, I don’t really know. My body remembers even when my mind can’t.

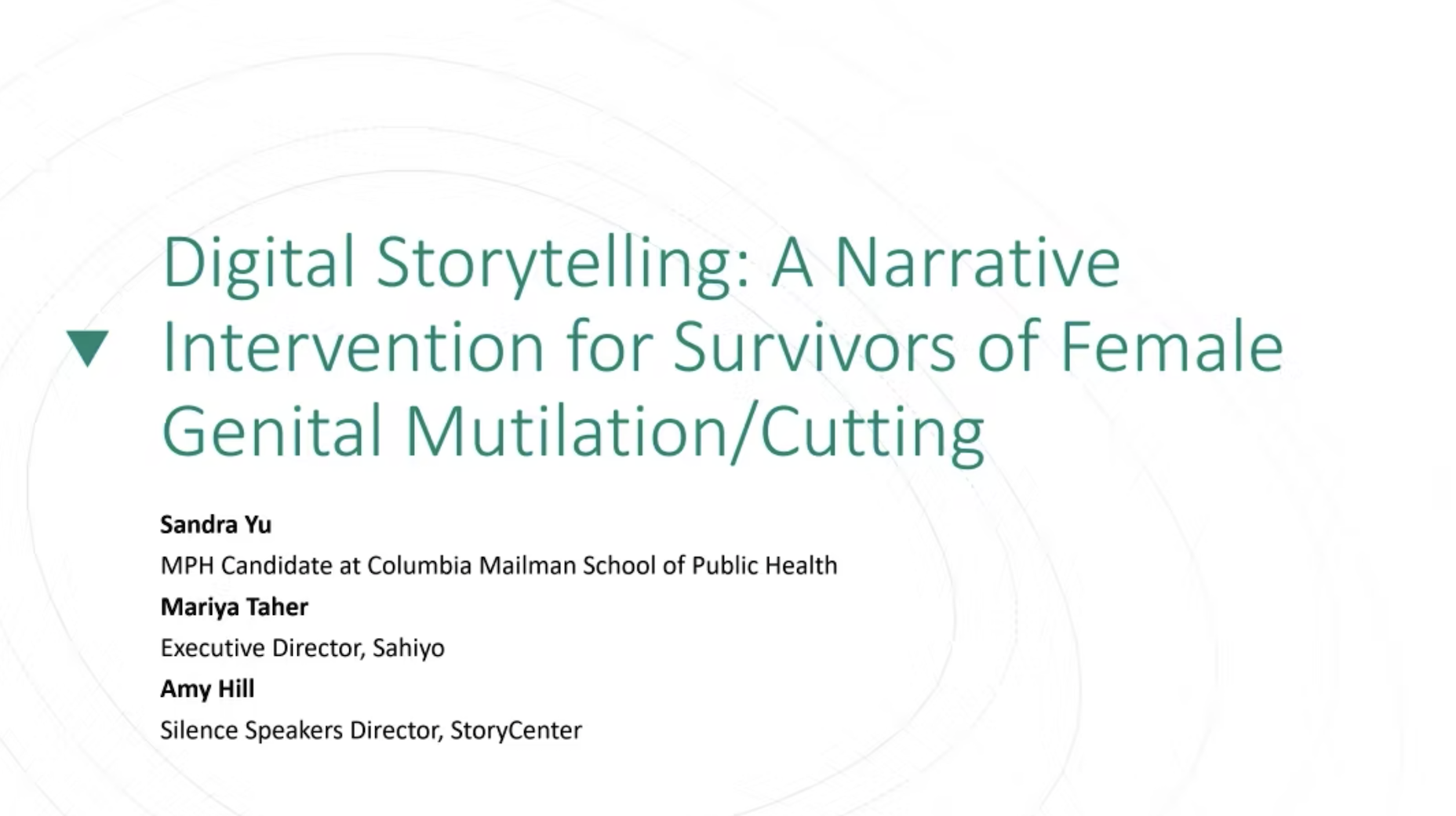

When I was in my early twenties and in a good mental space, I started asking about it. Family, community members who might have insight into the social atmosphere at the time, reporters, the judge who presided over the case. I looked over the court records for the first time. I learned about what had happened to me, what had really happened to me, through the stories of others. There are no words for what an odd, alien experience that was: to ask other people the details about one of the most intimate, traumatic, and developmentally defining experiences of my life. In all of my years of therapy and trauma research, I had never encountered other survivors who had to look outside of themselves, and to their community, to find the answers. Not until Sahiyo.

As I read their stories I found words for my own experience. I was able to so strongly identify with their grief and anguish that it felt like a physical tug in my chest. For every hour I spent wondering who I could’ve been without the weight of this sadness, someone else was working through that same struggle. And they were so brave and courageous, talking about their trauma with community members and advocating for childhood consent, working to eradicate FGC. You can't fully appreciate the strength it takes to speak openly about intimate trauma unless you’ve experienced it. These women are building a better world–both despite and because of what happened to them.

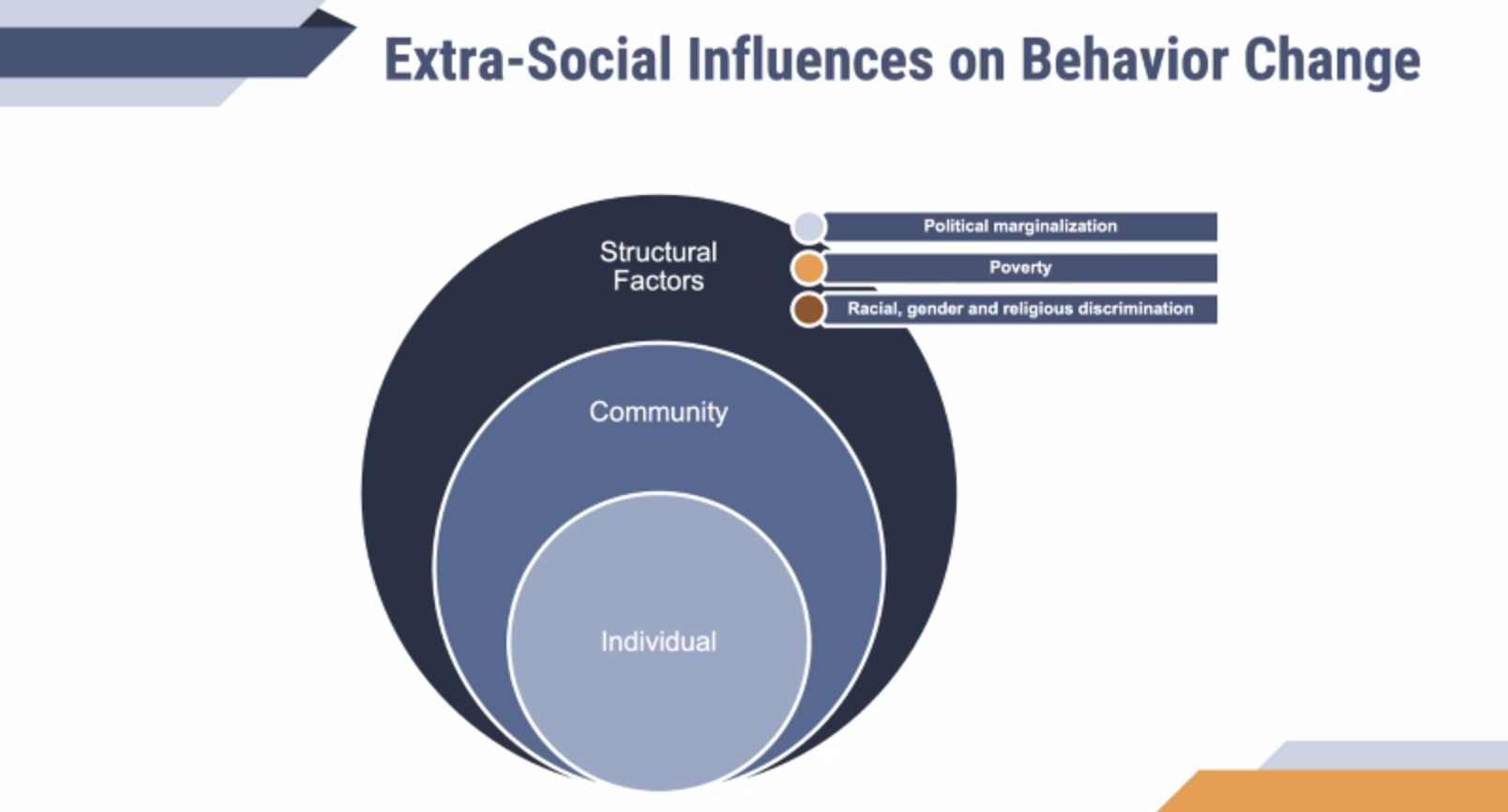

Our individual experiences are not the same. The weight of that generational trauma is not something I’m able to fully grasp, but I do know that I found courage and strength in their bravery. I know that I’ve reached a deeper place of acceptance with my own trauma. I choose patience, healing, and compassion just as I choose “survivor.” And that choosing is an act of defiance, of empowerment, of strength. It is both because of–and despite–what happened to me. The language of our internal world matters.

It’s always going to be hard. I wish that the world was a better place than it currently is. But if you are a survivor of childhood sexual abuse looking for a safe community of people who understand intimate body trauma, there is space for you here. Volunteering for Sahiyo means being a part of a global movement making the world safer and more accessible for women and girls from every background. It’s a worthy cause.