By: M Bohra

Age: 23

Country: United Kingdom

The ongoing investigation into Dawoodi Bohra doctors engaging in khatna, or female genital cutting (FGC), and the community leadership’s ambivalence regarding this practice, have once again brought up unanswered questions. What message is the leadership in India sending to the Bohra community when it disowns the doctors’ acts, not for their irreligiosity, but for their illegality in the West? Must the Bohra leadership accept the legal and moral responsibility of promoting khatna, especially since they advocate travelling to countries without FGM laws to continue this practice? Or can we expect them to continue throwing their misinformed, fanatical and grovelling followers under the bus to save themselves?

Many Bohris, in the privacy of their friends and families, will complain about the strict social norms that regulate every act of our lives within the community: where we pray, what we wear, who we do business with, what our family roles are, who we befriend, what we say, how we dissent, how we think. These criticisms are kept out of the community arena by the authoritarian diktats of the leadership. They hold the power to socially boycott (which, for many community-linked businesses is linked to economic loss), extort money for officiating religious ceremonies (including permitting travel to the Hajj pilgrimage), and even denying burial in Bohra cemeteries. While we continue to chafe under this authoritarian religious regime, however, we must acknowledge our own prejudices.

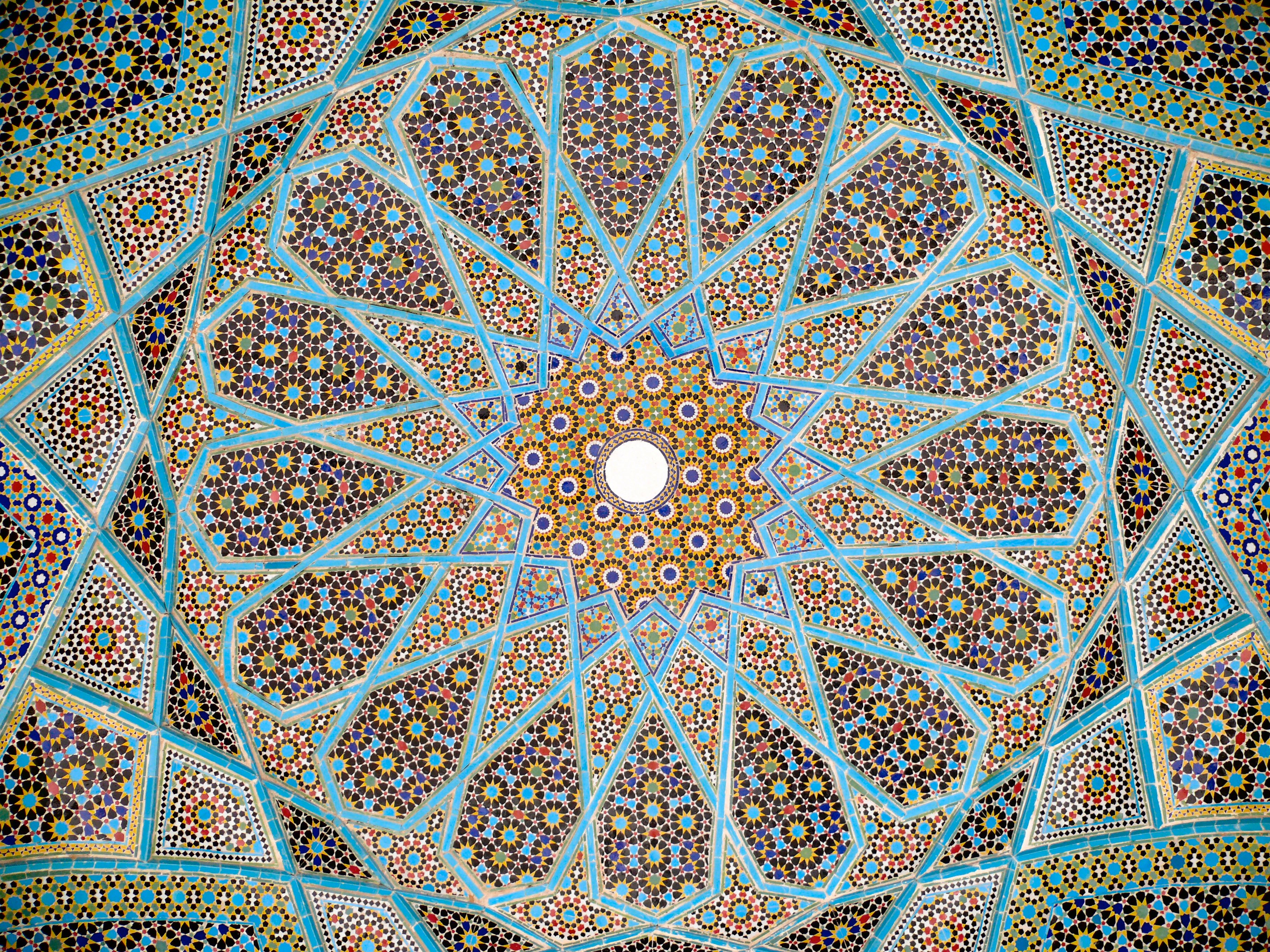

Bohris, despite all evidence, believe that we are God’s chosen people. We consider ourselves not only superior to non-Muslims (which is a broader Islamic problem), but even non-Bohra Muslims. We call our own community “mumineen” (the believers), and the others “musalmaan”. Even other Shia groups are generally only respected during the first ten days of Muharram, when we enthusiastically join our “Shia brothers” in the Ashura processions and sermons, only to exclude them from our lives on the eleventh day. We consider our mosques cleaner, our prayers more spiritual, and even our cemeteries as somehow more special. We are “blessed” to be ruled by tyrants, who guarantee us a heavenly afterlife in exchange for worldly money.

Are we surprised that the leadership continues to promote a domesticated and desexualised ideal for our women, when it promotes a passive and unintellectual ideal for our men? It is important to remember that their power comes from our submissiveness, which is the result of our own prejudices. We need to introspect and question the foundations of our own biases. What is unclean about a non-Bohra mosque? What is inappropriate about performing the Hajj without being led by a Bohra priest? What is the problem with marrying outside the community? Can Bohra women question the religiously-sanctioned ideal of making rotis and handicrafts confined to their homes? Why do we have to control women’s sexuality through physical means, but not men’s? If the current system is broken and cannot be reformed, are we ready to create new religious and social spaces with other disillusioned Bohris? Can we create new inclusive and non-hierarchical spaces to end religious dogmatism, bring financial accountability, provide spiritual healing and engage in progressive social reform without prejudice?

Here’s a little history lesson to conclude this piece. The office of Dai Al-Mutlaq, which is currently held through hereditary means by Mufaddal Saifuddin, is not the same as the position of the Imam, who is considered as the rightful spiritual and political successor of the Prophet in all Shia traditions. The first Dai was appointed by Arwa Al – Sulayhi, a long-reigning queen in Yemen, as a vicegerent (deputy) for the young Imam At-Tayyib. The succession of Dais was not always hereditary, and was likely based on spiritual and political merit. Increasing persecution drove the leadership to settle in Western India, where they were welcomed by a community of religious converts. Note how the position of the Dai was created by a powerful woman ruler (who probably wasn’t told to make rotis and handicrafts), not as a hereditary office, and owed its continuity to the goodwill of the new community of Bohris in India. Over the centuries, the leadership has forgotten who was in charge. It’s time for a reminder.

The first time we were intimate she began crying uncontrollably. She told me what had been done to her. She herself didn’t know what had been done to her until she learned about it in college. She felt an electric shock like pain down to her toes when it was done, but I was the first to be rocked by the waves of that ripple effect. She felt scarred and damaged. She wanted so bad to connect with me intimately, but it could never happen. That had been stripped away from her along with her ability to be a complete woman, against her will, as a minor. We worked through it together. I went to her counseling appointments. I reassured her that our love would only grow stronger, but she and I both knew no one could ever give back to her what was lost in that moment.

The first time we were intimate she began crying uncontrollably. She told me what had been done to her. She herself didn’t know what had been done to her until she learned about it in college. She felt an electric shock like pain down to her toes when it was done, but I was the first to be rocked by the waves of that ripple effect. She felt scarred and damaged. She wanted so bad to connect with me intimately, but it could never happen. That had been stripped away from her along with her ability to be a complete woman, against her will, as a minor. We worked through it together. I went to her counseling appointments. I reassured her that our love would only grow stronger, but she and I both knew no one could ever give back to her what was lost in that moment.