Should mild forms of Female Genital Cutting (FGC) be legalised? Should supposedly “harmless” nicking or slicing of clitoral tissue be medicalised, simply because getting communities to completely stop FGC happens to be a very difficult task?

There has always been some support for mild, medicalised FGC, chiefly from communities that claim to practice female “circumcision” and see it as completely different and divorced from any form of genital “mutilation”. And for years, this view has been firmly refuted by survivors and activists who don’t want any girl to experience the trauma, betrayal and potential harm that even the least severe forms of FGC can cause.

But recently, support for mild, “symbolic” genital cutting came from the most unexpected source – The Economist, a prestigious weekly news magazine headquartered in London.

In an editorial on June 18, titled ‘An agonising choice’, The Economist presented a baffling argument: since global campaigns to bring about a “blanket ban on FGM” have been unsuccessful for 30 years, it is “time to try a new approach”, in which governments could ban the “worst forms” of genital cutting and instead “persuade” parents to choose the “least nasty version”.

“However distasteful, it is better to have a symbolic nick from a trained health worker than to be butchered in a back room by a village elder,” the article says.

As was to be expected, The Economist has since faced some much-deserved backlash from indignant survivors and activists. Several NGOs and media publications have termed The Economist’s stand as irresponsible, and UK-based NGO Orchid Project has also started a petition to get the magazine to withdraw the article.

But a disturbing response – in praise of the irresponsible article – has emerged from some quarters of the Dawoodi Bohra community.

The Bohras predominantly practice the “mild” forms of FGC that The Economist has advocated for – slicing off the prepuce or clitoral hood, and in some cases, nicking or pricking of the prepuce. And in the past few days, some Bohras began to circulate Whatsapp messages amongst themselves claiming that “for the first time, a prestigious paper writes something in our favour, and has challenged WHO and the anti-FGM lobbyists”. (Even The Guardian has mentioned this response from conservative Bohras in its report on the negative impact of The Economist’s article.)

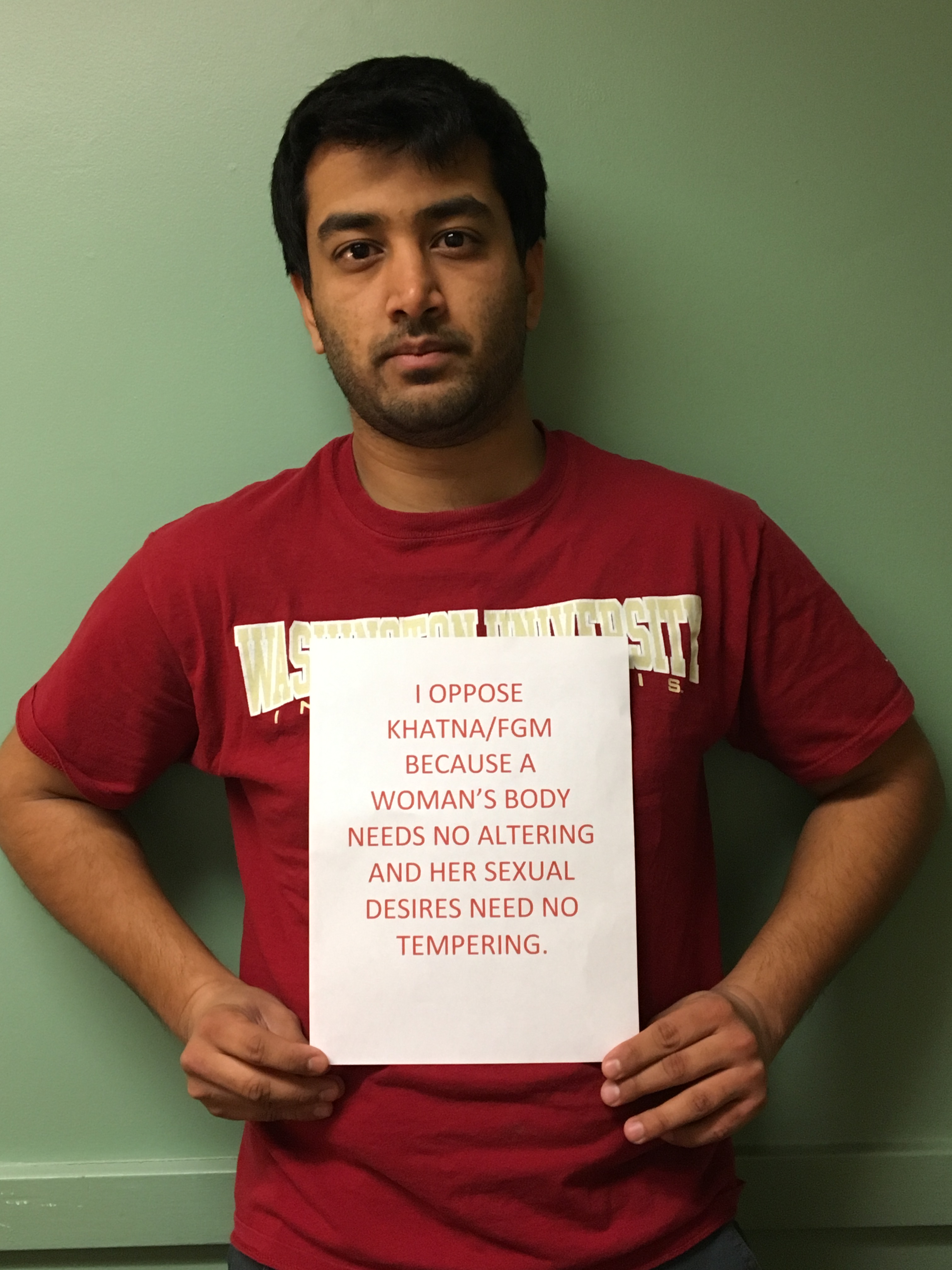

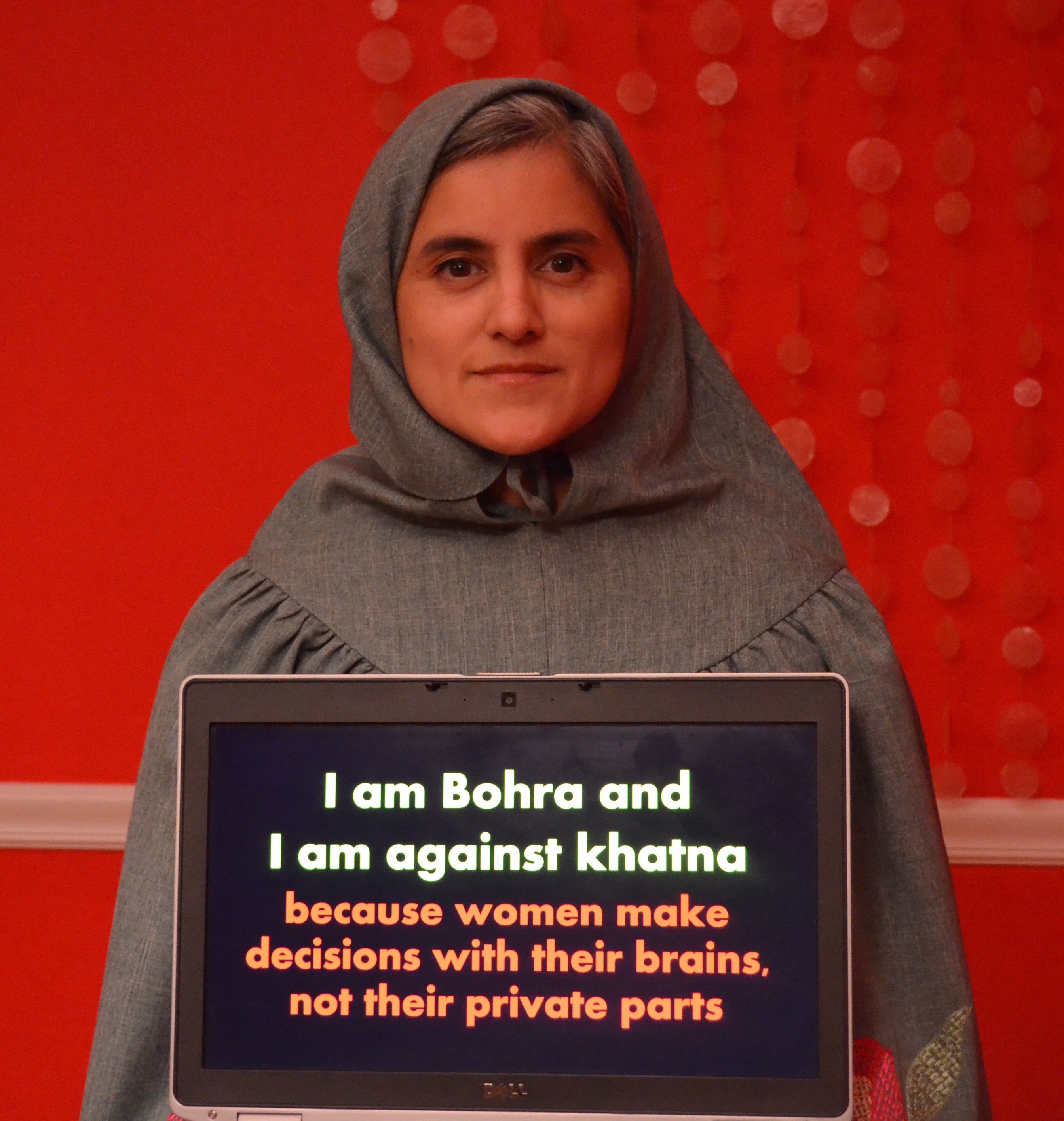

In this context, it is more vital than ever for us in the Dawoodi Bohra community to speak out against such misguided views. Should activists like us agree to “compromise” for the sake of respecting cultural traditions? Should we condemn female genital “mutilation” – the severe forms that involve cutting the whole clitoris and more – while condoning female “circumcision”? Should we say it is okay for Bohras and other communities to let medical professionals snip off a mere little pinch of skin from a little girl’s clitoral prepuce?

Our answer is a resounding NO.

Even the mildest, most “symbolic” type of female genital cutting is a form of gender violence. A significantly large number of Bohras cut their 7-year-old daughters because they believe it is a means of controlling a woman’s sexuality. If a girl is not circumcised, they say, she will have stronger sexual urges and she is likely to have pre-marital or exra-marital affairs. What is this if not blatant patriarchy, which denies women a right to their own bodies and attempts to police her “character”?

Then there is a growing section of Bohras who claim that the circumcision they practice is merely “clitoral unhooding”, a procedure that they claim enhances sexual pleasure by exposing the clitoral glans. There are many things wrong with this argument. One, clitoral unhooding is a medical procedure that some adult, sexually active women can choose to undergo if they have excessive prepuce tissue that happens to interfere with orgasms, whereas “circumcision” is done on all young, sexually inexperienced girls, without their consent,even if their prepuce tissue is not excessive. Unnecessary removal of the clitoral hood could leave the clitoris vulnerable to abrasions or over-stimulation.

But the other major issue with promoting “unhooding” is the supposed reason behind it. Altering a little girl’s genitals in order to “enhance” her adult sexual life is also a form of trying to control a woman’s body without her consent. Once again, it amounts to gender-based violence.

Of course, there are also Bohras who claim female circumcision is done for religious “purity” and cleanliness. This is laughable. In a community that places so much emphasis on taharat (hygeine) and washing one’s genitals thoroughly during “istinja”, do we really need to cut off a little bit of natural skin tissue simply in the name of cleanliness? The argument simply doesn’t stand.

If The Economist and its supporters believe that “mild” FGC is so harmless, then why do it at all? What is so repulsive about that little tip of God-given skin that entire communities are willing to fight the tides of progressive change in order to retain their culture of snipping it off? Why do these communities choose to dismiss the voices of the women who have suffered physically, psychologically and sexually because of these very “mild” cuts? Why do communities insist on getting into a girl’s underpants instead of staying out of them?

Ultimately, one cannot escape the fact that any form of FGC is an attempt to control women’s bodies and, by extension, their minds and beings. Allowing supposedly symbolic FGC to continue will not solve this problem.

And finally, a word on The Economist’s defeatist attitude: did anyone really expect a deep-rooted practice like FGC to come to a complete halt after just 30 years of campaigning? If social change were possible that quickly, America wouldn’t be struggling with racism 50 after the Civil Rights movement, India would not be seeing rabid casteism nearly 70 years after Independence, and women wouldn’t still be fighting for their most basic rights.

If we opt for compromise simply because the fight for an FGC-free world is so exhausting, we would be failing future generations of little girls who will continue to be violated without their consent.

Call to action: You can make your voice heard by signing Orchid Project’s petition against The Economist’s irresponsible stand. Sign the petition here.